Every January 26th, we celebrate the remarkable document that gave our diverse nation a common soul. The wisdom of Dr. Ambedkar and the Constituent Assembly created a framework resilient enough to guide India for over seven decades. But what if history had taken a different turn? What if the monumental task of drafting our Constitution had been entrusted entirely to the women of India? While this is a counterfactual exercise, exploring it isn’t about diminishing our actual founding fathers, but about understanding how a different lens might have shaped our nation’s foundations in subtle, practical ways.

Women Who Would Have Done It

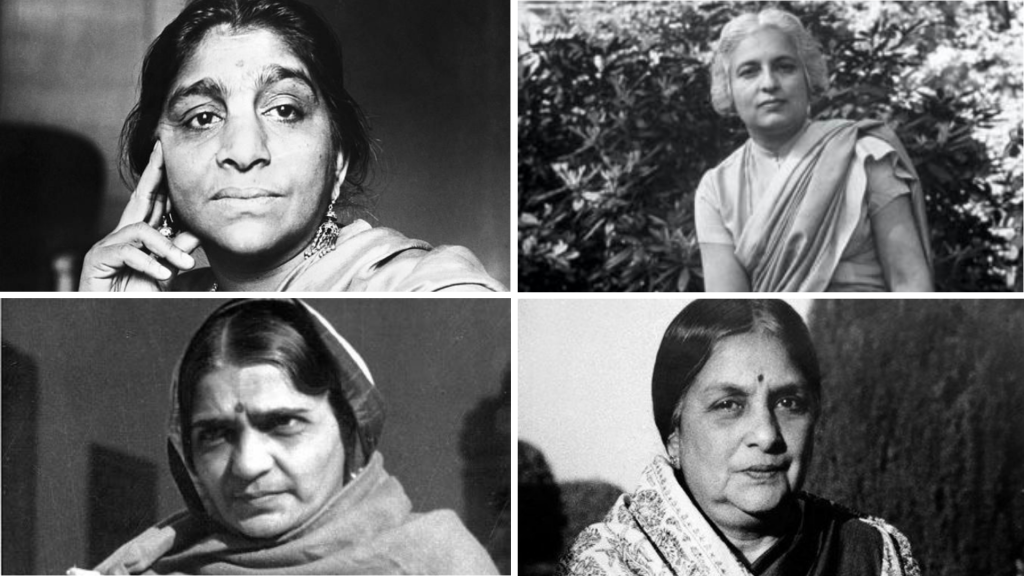

In the 1940s, the Constituent Assembly had 15 remarkable women members, including figures like Sarojini Naidu and Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit. Their contributions, though significant, were voices among hundreds. Imagining a document written solely by women means envisioning a council composed of not just these political leaders, but also of educators like Hansa Mehta, social reformers like Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, and perhaps even incorporating perspectives from grassroots shakha leaders, nurses, farmers, and artists. Their lived experiences, of familial law, economic dependence, and social constraints, would have inevitably shaped the text’s priorities.

A Different Set of Core Principles

The most immediate and practical change would be visible in the Directive Principles of State Policy. These guidelines, which are not legally enforceable but fundamental to governance, might have seen a profound shift in emphasis. We could expect a much stronger, more detailed focus on social infrastructure from the very beginning. The right to education, especially for girls, would likely have been framed as an urgent, non-negotiable state duty, potentially accelerating its implementation by decades. Healthcare, particularly maternal and child health, might have been positioned not as a welfare scheme but as the bedrock of a productive society. This perspective would have made laws against crimes like rape inherently more victim-centric and focused on trauma-informed justice from the very beginning. The clause urging the state to secure a living wage (Article 43) might have been explicitly linked to equal pay for equal work, a principle Indian women still advocate for today.

Stronger Laws for Equality & Safety

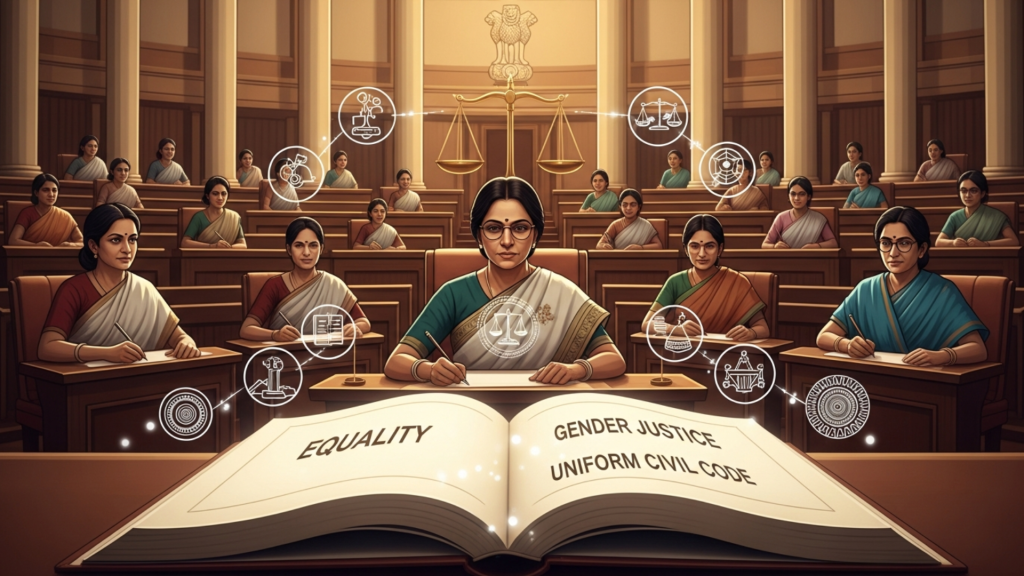

The chapter on Fundamental Rights would have retained its core freedoms but might have been fortified with more specific guardrails. The right to equality (Article 14) could have been accompanied by a clearer, more robust clause explicitly prohibiting discrimination on grounds of sex, closing legal loopholes from the start. The most transformative change, however, would likely have been in the realm of personal laws. A women-led assembly, intimately aware of the disparities in marriage, divorce, inheritance, and adoption across communities, might have had the political will and moral authority to implement a Uniform Civil Code from the republic’s first day. This single act would have altered the social landscape of modern India, establishing a principle of gender justice in the family sphere as a foundational, rather than a perpetually debated, ideal.

One Law for All Families from the Start

The architecture of governance might also have looked different. Inspired by the Gandhian principle of Gram Swaraj, which many women leaders championed, Panchayati Raj institutions could have been constitutionally mandated and empowered from 1950 itself, not in 1992. Furthermore, it is reasonable to speculate that a draft put together by women would have institutionalized their own political participation. A constitutional provision for significant reservation for women in legislatures could have been a founding feature, dramatically altering the composition of Parliament and state assemblies for the last 75 years and normalizing women’s leadership in executive roles much earlier.

An India Built on Different Foundations

Would the spirit of the document be different? Perhaps. The Preamble’s fraternity might have been imbued with a stronger sense of collective care and community responsibility. The state might have been envisioned not just as a neutral referee, but as an active nurturer, investing in the health and education of its citizens as the highest form of national security.

Same Tough Challenges

Yet, it is crucial to be practical. This hypothetical constitution would not have been a utopian document created in a vacuum. These women would have faced the same immense challenges of partition, mass migration, and integrating princely states. They would have had to negotiate with the same array of regional, linguistic, and religious interests. The resulting document would still be a brilliant compromise, but one where the compromises were made with a different set of non-negotiables at its heart.

Why This Thought Experiment Matters

On this Republic Day, such an exercise reminds us that our Constitution is a living tree. The seeds planted by our founders have grown, and we continue to shape its branches through amendments, judicial interpretations, and our daily civic actions. Imagining a constitution by women underscores a simple truth: the lens of lived experience shapes policy. It challenges us to ask whose experiences continue to be underrepresented in our national dialogue today, and how we can ensure that the quiet, practical wisdom of all Indians finds its way into the ongoing story of our republic. The goal is not to reinvent our past, but to build a more inclusive future, guided by the spirit of justice, liberty, and equality that defines us all.