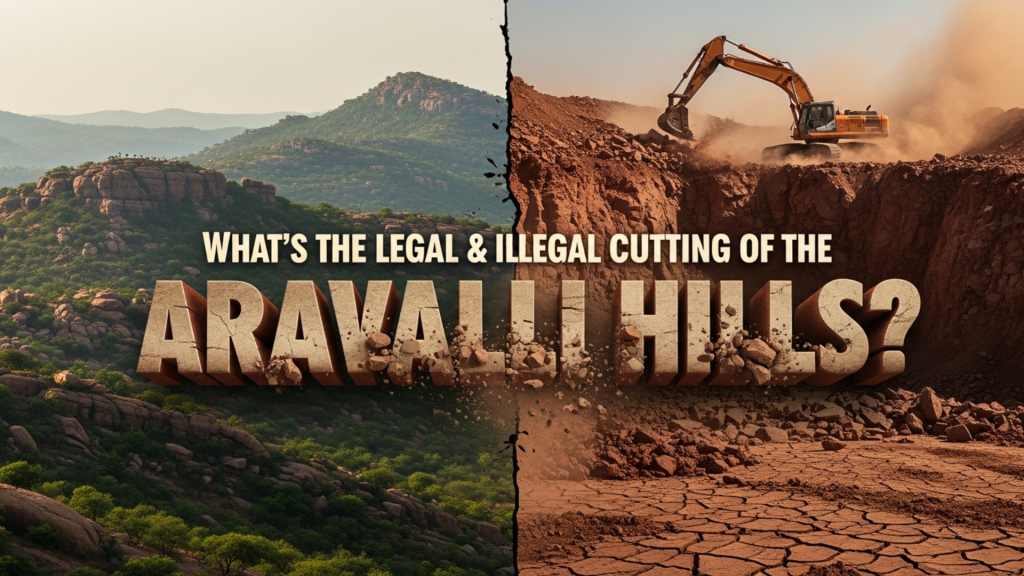

Humankind is in danger, wildlife is in danger, and the entire ecosystem is going to lose its vital balance. If you live in or follow news from North India, particularly the National Capital Region (NCR), you may have come across a persistent and concerning phrase, i.e., the cutting of the Aravalli Hills. It doesn’t refer to a natural process of erosion, rather to a man-made one. It’s a term that encapsulates a significant environmental crisis. The question is what it means for the millions of people who depend on this ancient mountain range.

What Are the Aravallis, and Why Do They Matter?

First, it’s important to understand what the Aravallis are. They are one of the world’s oldest mountain ranges, older than the Himalayas, running approximately 670 kilometres from Gujarat through Rajasthan and into Haryana and Delhi. For centuries, they have acted as a natural barrier against the expansion of the Thar Desert into the fertile plains of the Ganges. They are not towering, snow-capped peaks, but rather a series of ridges and hillocks, rich in biodiversity and forest cover, crucial for groundwater recharge.

What are the Mining and Real Estate are the Primary Reasons

The cutting here means the large-scale physical removal of these hills with the help of heavy machinery. And this activity is primarily driven by two interconnected demands.

Demand for Construction Material: Those who know would know that the Aravallis are rich in quartzite. It is a hard stone that is crushed to make gravel and sand for the construction industry. It’s also known as bajri, and is a key component of concrete. With relentless urbanization, the building of housing societies, commercial complexes, and infrastructure projects across the NCR and Rajasthan has created an insatiable demand for this cheap, easily accessible material. Mining, both legal and illegal, has become a profitable industry. Anyway, companies with mining licenses generally ignore the rules. They dig up much larger areas than they are supposed to, cutting away entire hillsides.

Pressure for Urban Expansion: The land on which these hills stand is increasingly seen as prime real estate, especially in areas like Gurugram and Faridabad in Haryana, and certain parts of Rajasthan. Flattening hills clears the way for spread-out residential townships, shopping malls, and golf courses. This land is categorised as gair mumkin pahar (uncultivable hill)) in old revenue records. And that’s why it becomes a target for developers seeking to expand urban frontiers. Developers get the rules changed by arguing that the land isn’t a real ‘forest’ or ‘hill’ (as defined by law). And then these controversial changes are frequently challenged in court.

What are the Consequences of Cutting the Aravalli?

The impacts of cutting the Aravallis are severe and multifaceted.

Ecological Collapse: These hills are a fragile ecosystem, home to species like leopards, hyenas, and hundreds of birds. If they destroy their habitat (which they’re doing), it fragments wildlife corridors and pushes species toward local extinction.

Water Scarcity: As a result of cutting down the Aravalli range, it directly worsens our severe water shortage. The hills soak up rainwater to refill underground natural reservoirs. When that land is paved over, the rain just washes away and is lost.

Increased Air Pollution and Dust Storms: The Aravallis are a natural windbreak. Their removal allows dust from the Thar Desert to travel eastwards unstoppable. And contribute to the intense dust storms and poor air quality that plague the NCR.

Loss of Green Lungs: The scrub forests are vital carbon sinks. Their removal reduces the region’s capacity to clean its air and mitigate local temperatures.

A Legal Battle with Weak Enforcement

1. The Existence and Date of the 2025 Judgment:

In a landmark July 2025 ruling, the Supreme Court of India expanded the protected ‘forest’ status to the Aravalli hills in Rajasthan and mandated a 100-meter-wide ‘no-mining, no-construction’ buffer zone around them. The Supreme Court of India delivered a crucial judgment on July 18, 2025, in Civil Appeal No. 4567 of 2023 (Kantor and Sons Pvt. Ltd. & Anr. vs Union of India & Ors.).

2. The Core of the 2025 Ruling (Extending the "Forest" Definition to Rajasthan):

This is the central holding of the judgment. The Court ruled that the broad “dictionary meaning” of forest established in its 2018 order for Haryana’s Aravallis must also apply to the Aravalli hills in Rajasthan.

3. The Impact (Granting Higher Protection, Restricting Mining):

By classifying these areas as “forest” under the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980, any proposal for non-forest use (such as mining, construction, or clearing) now requires prior approval from the central government. This places a major legal hurdle in front of new mining leases and other developmental projects in the Rajasthan Aravallis, strengthening their protection.

A Major Legal Reversal and Stay (2025-2026)

Important Update: The legal landscape shifted dramatically in late 2025. On November 20, 2025, the Supreme Court issued a controversial verdict that sought to narrow the protective “forest” definition for the Aravallis, notably by introducing a restrictive “100-metre rule.” This ruling triggered widespread public outcry and environmental concerns. Consequently, in January 2026, the Supreme Court took suo motu cognisance and stayed (paused) its own November verdict. The 2025 judgment is now in abeyance, pending a fresh expert review. This underscores the ongoing, volatile nature of the legal battle for the Aravallis, where protections remain in a state of flux despite previous progressive rulings.

A Trade-Off with Long-Term Costs

In conclusion, the cutting of the Aravalli Hills represents a profound trade-off. It prioritizes short-term economic gain from construction and real estate over long-term ecological security. We are consuming a non-renewable geological formation that provides essential services, water security, clean air, climate regulation, and biodiversity.

The hills are being cut because they are valued more as a commodity than as a life-support system. It’s a blunder for humankind and wildlife as well. The critical question is if this consumption will be checked in time, before the ancient barrier that has shaped North India’s ecology is lost beyond repair.